You can't tell Rusyns they're Ukrainian, says the most famous Gelding from a TV ad

We met President Zelensky as colleagues at the premiere of the film The Line in Kyiv. He's a nice guy, says Ukrainian actor Eugene Libeznyuk.

An actor at the Alexander Dukhnovich Rusyn Theatre in Presov and the most famous Gelding from the TV commercial, Eugen Libeznyuk (62) recalls his childhood in Ukrainian Bukovina, his bohemian life during his studies in Kyiv, and his military service in Briansk, Russia, where Ukrainians were referred to as banderos. Some of his Ukrainian classmates had already fallen during the Russian aggression.

"The first time I heard the term Moskali referring to Russians was when I was a little boy; it reminded me of the word ruskal, which meant spade," Libeznyuk says.

In the interview you can read:

how his uncle in Bukovina remembered Czech financiers calling him "you kid."

what role vodka played in the national movement;

what shocked him when he came to Slovakia after his studies in Kyjov;

that they couldn't have Christmas under the Soviet Union and jeans cost six months' salary;

what his relatives in Ukraine say about the Fico government's refusal of military aid.

What kind of groceries do you go shopping for?

To the ones that are closest. I joke that I am banned from an unnamed chain because everyone thinks I get a discount there. It happens that people want an autograph or even more often a photo together. This is one of the longest running commercials we've shot, I think we started our fifteenth year.

You come from Bukovina, Ukraine. How would you describe your hometown of Kicmany?

I lived there until I was eighteen. The most beautiful period of my life, every nook and cranny I knew. I was born near the forest, as a boy I spent every day there. The forest is no more, it has been replaced by a road.

How did the war affect Kicman?

The town has about 10 thousand inhabitants. Since the beginning of the Russian aggression in February 2022, the population has increased about fivefold. People have come there from parts of Ukraine where fighting is taking place, staying wherever they can; in schools and dormitories.

Did your relatives and friends enlist?

Of course, some of my classmates have fallen too. Recently I was shocked by the news that eighteen kilometres from the front line they were giving decorations to members of the Carpathian Mountain Brigade, which the Russians took advantage of and attacked with a rocket. This resulted in dozens of casualties.

Bukovina, where you come from, was the easternmost part of the Habsburg monarchy. Then it belonged to Romania, to the Soviet Union, to what is now independent Ukraine. People did not even have to leave their homes and found themselves in different countries. How did that affect your childhood?

It was strange for me as a kid to listen to my grandmother's house and they would say "well, under Romania" or "under Austria". I didn't understand, I was born in the Soviet Union. Only later did I understand. For example, my uncle was still living in Czechoslovakia, and when he came, he used to tell us, "I remember when I was a boy, Czech financiers used to come to our house and call me 'you kid'." That's what he remembered, the older people in our country understood Czech. Under Masaryk they lived the best. The elders used to say to me: "That was a different world, we didn't accept the Soviet era then."

Recently I was in Chernivtsi, the capital of Bukovina. I was charmed by the university, more beautiful than Oxford and built by a Czech builder. But the grandfather at the concierge reminded me of Soviet times, when he wouldn't let me and my daughter in as "individual tourists", saying that only in a group...

I guess you were in the summer when the university management was not present, then who is the director? The gatekeeper. The centre of Chernivtsi is reminiscent of Vienna or Prague, it's an old European city. Chernivtsi was not included in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1938, but Stalin took it, which made Hitler very angry, as there was a large German community living there and they had to move out. Romania, to which these territories belonged until then, did not protest.

The Austrian writer Martin Pollack writes excellent historical accounts of Halycha and the adjacent territories, drawing on the rich archives in Vienna. He reports that 160 newspapers from the metropolises of Central and Eastern Europe could be read in a café in Chernivtsi.

It was a fantastically advanced town, a crossroads of trade routes. Part of the large Jewish community there survived the Holocaust, many then emigrated to Israel in the 1970s.

Do you identify as a Ruthenian or as a Ukrainian?

Sometimes I say that the cow forgot she was a calf. Just as Ukrainians eat their hair when their "elder brothers" Russians tell them that they are one people, Rusyns are bothered when Ukrainians think of them as Ukrainians. Whenever someone else decides who you are, it causes resentment. I say let them call themselves whatever they want. I am a native Ukrainian, but I am very proud of myself for helping Rusyns here in the region.

I remember that in the late 80s we were playing with a theatre in Košice, we were speaking Ruthenian with each other, a waiter came and asked, "Do you speak our language? If I spoke like that, I'd be fired from my job." At that time you couldn't admit to being a Ruthenian, you could only be a Ukrainian. Someone had decided that directly under socialism. It's always bad when someone else decides about a person. Do you want to claim to be an Eskimo? It's your right. You can't call Rusyns Ukrainians. At home we spoke Ukrainian, I've been learning Ruthenian for thirty years.

When I came to Presov from Kyiv in 1986, it was the Ukrainian National Theatre until 1991, where Ukrainian was spoken. However, we used to speak Ruthenian among ourselves, I only learned that here. The only Slovak word I knew was ahoj-hello.

That was enough.

Because when we said goodbye, we said nashledanou-goodbye. There was Czech and Slovak on the TV at that time, which I took as one language. On the street they spoke Shariš, my sentences were in two or three languages.

Your Slovak teacher was the "dramaturk" of the theatre, as you wrote, Vasil Turok. A peculiar man, now deceased. When we went in 1997 with the cartoonist Fedor Vico to look for Rusyns in Transcarpathia, Turok was sitting in the theatre "buffet" with a bottle of vodka. Well, when we returned three days later, he was sitting with vodka in the same place. After his death, they made a memorial to him in a bistro in Presov, a marble pedestal with a half-cup of vodka on it.

Yes, in Agata. Vodka played a big role in the national movement. It was a life-giving drink, it relaxed people, loosened their tongues, allowed them to express their opinions freely.

What was life like in the 1980s in Kyiv, where you studied at the Karpenko-Kare Theatre Institute? My anthropologist friend Saša Mušinka, who is younger than you, told me about the exuberant life at the boarding school.

Well, yes, it was cheerful there. Worse was that as actors we spent all our days from morning till ten o'clock in the evening at school. There were only parties at night, but by then we were tired. We slept very sparingly. Among the younger ones at the school was, for example, the actor Mišo Hudák.

Look, I say that life is the same everywhere at a certain age. Student age is a golden time. Why do many Russians support Putin in his efforts to restore the empire? They don't support the soyuz, but they want to return to their youth, to the golden age when everything was in front of them and life seemed to have caught them by the scruff of the neck. Then the regime was breaking them.

When you go on a train and after an hour you are in another country, you have the idea that something is ending here and something else is beginning. But when you get on a train and after a month you are still in the same state - which was the case in the Soviet Union - but you have travelled 9 thousand kilometres, you have a different scale and perception.

Have you travelled Union cross-cross?

No, unfortunately I didn't. But I know the central part, I served in the war in the Russian Briansk region. The first time I went to Europe, as we used to call Czechoslovakia, was in 1985. By then my first wife Tatiana and I had a son. I applied for a place in the theatre, they were happy to take me.

And at the same time, I had been learning English in the soyuz since the fifth grade, which I had no place to use. But you have to know the language of the imperialists. We had one more hour of Russian than Ukrainian at school. In between was English, an hour a week.

How did it feel for you to come from the Soviet Union to Czechoslovakia?

It was a colour shock, there was a Soviet greyness in our country, especially in the villages. It was done in such a way that you couldn't see the houses, they blended in. There was no individualism, it blended in. I remember that when I crossed the border and found myself in Michalovce, the first thing that struck me was the colourfulness of the houses, the roofs of a different colour, the flowers planted in the streets - that was not the case here.

What attracted you to Slovakia when you arrived, apart from the colourfulness?

I'm thinking... In the Soviet Union under Gorbachev, under glasnost, there was paradoxically more openness than in your country. I went to school under Brezhnev, that was a hard regime. Then it came here too. When the director Blaho Uhlar came to Prešov and did a performance here, for example Sens nonsens, which we performed for colleagues from other cities in Slovakia on Theatre Day, after the performance many people were amazed: 'They allowed you to do that?

In what other ways did you perceive differences between Ukraine and Slovakia?

Of course, in the way of life. Here, as I say, there was no unnecessary secrecy, you didn't have to hide your expressions. I was taken aback when I came here and Christmas was being celebrated here.

Wasn't that yours?

No way!I asked my wife:Is that allowed in your country?As a child, I used to go trick-or-treating in the village - but only in the family.My mother always said:No, you don't say that at school.In the village it was still OK to carol, in the towns not at all.Mum said: There goes so and so and so and writes down who carols, for the party organs.In the village people were religious, in the city less so.In the center of Kicman, for example, they made a temple into a business center, a univermag, under socialism. In the village where my grandmother lived, they turned the church into a museum of cosmonautics. After the fall of the regime it came back, people came there and asked for the return of the temple, that was under Gorbachev.The chairman said that it was not going to go just like that, because they had invested a lot of money in the museum.The next day the villagers brought him the necessary amount.

Seriously?

They raised it.There was nothing to buy in the shops, people kept the money at home.Jeans cost more than a month's salary and could only be bought on the black market.Jeans were a dream of something unattainable. You couldn't just buy it.The salesman didn't just sell it to you, you had to go through someone who knew him and recommended you.A Japanese cassette recorder cost in the bazaar from a thousand rubles upwards, six months' salary. The man who had it was king.

You were wearing jeans?

Yes, but Soviet.We peeled them with a brick as best we could, but they held their color, which annoyed us.

I remember in the '90s a little shop in Bolshoy Bereznye in the Ukraine across our border.The top shelf was just pickles, the middle shelf was empty, and the bottom shelf had a bucket with a sign that said clean water...

This is possible, but the manager apparently faced criticism for this, asking why he didn't have pickles in the middle rack as well, since it couldn't be empty.

Did you already perceive the national tensions during the Soviet Union, the historical wrongs inflicted on Ukrainians by Russians?

When I was a little boy, the first time I heard the term moskali.That's how they referred to Russians.It reminded me of the word ruskal, which meant spade.I asked: What kind of spades are we talking about?Then I encountered nationalism in the military. When I joined in 1979 in Briansk, Russia, the first thing they asked me was where I was from. When I said from Ukraine, I was a Bandera.They didn't even call me anything else.The word had a very negative connotation.We were not fascists for the Russians then, only banderovtsy.

You were a ghost for the first six months of your military service, you had no rights. The second half of the year you were already young.The third semester you were a nigger, a scoop, you got your ass kicked twelve times with it.Last six months you were a grandfather, nobody had it in for you.Then, since demobilization, you've been a "dembel".

Did the Russians make it clear even then that Ukraine had no right to exist, that Crimea belonged to them?

There were no such debates under socialism, that was the Soviet Union.The Russians treated everyone else like an elder brother, they felt like something more.Back then in our Bukovina it was the case that in the villages they spoke Ukrainian, in the towns Russian, it was a sign of higher culture.

It's such a Jewish joke. Moshe says to Abraham: I think I'll start speaking Ukrainian.Why?Are you afraid the Ukrainians will beat you up?Abraham asks. Oh no, I'm afraid the Russians will come to liberate me, Moshe says.

From Slovakia, how did you experience Maidan, the biggest uprising of Ukrainians for freedom?

I like it immensely when people stand up to tyrants.President Yanukovych refused to sign the association agreement with the EU, people took to the streets, it was cold, and they did not allow it, they did not retreat.

Were you taken aback by Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, then by the war in the Donbas?

Not really, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was heading towards that. They have always had Crimea as theirs, an independent Ukraine is a misunderstanding for them. There is an expression in Russian for 'vremennoye pomeschestvo', temporary insanity, one day we will do something right with that Crimea too.

Is it true that you know Volodymyr Zelensky personally?

Yes, as colleagues we met in Kyiv before he became President. A nice guy. In 2016, at the premiere of film The Line, his co-producer and now head of his office, Andriy Yermak, introduced us to him.

You're certainly in touch with loved ones in Ukraine. What do they say about the new Fico government's refusal of military aid?

They know it, it's incomprehensible to them. They took us as the ones who helped the Poles the most, they don't understand this turn of events. They do not condemn the Slovaks in Ukraine, they condemn Fico.

Andrej Bán

Orginal version:

https://www.rusyn.sk/nemozes-rusinom-hovorit-ze-su-ukrajinci/

Translation by deepl com

Aktuality

Zobraziť všetky20.07.2024

Významná postava kultúrneho života Podkarpatskej Rusi

KAIGL Ladislav (*10. 12. 1885, Praha - †1. 1. 1939, Rakovník), český správny úradník, maliar a pedagóg. Tesne pred prvou svetovou vojnou odišiel za prácou do Ruska, kde učil na gymnáziách. Počas vojny sa prihlásil k československým légiám a s ni…

17.07.2024

V Užhorode vysvätili nového gréckokatolíckeho biskupa

Po štyroch rokoch a dvoch dňoch bez sídelného biskupa dostala Mukačevská gréckokatolícka eparchia na Ukrajine svojho nového pastiera. Stal sa ním otec Teodor Macapula IVE, člen rehoľného Inštitútu vteleného Slova. Biskupská chirotónia (vysviacka…

16.07.2024

Klidný, vyrovnaný, připravený šel před 75 lety generál Heliodor Píka na popravu

Syn Milan Píka strávil s otcem poslední noc před jeho popravou, byl oběšen ráno 21. června 1949. „Není ve mně zloby, studí mne však hořká lítost nad tím, že zmizela spravedlnost, pravda – snad jen dočasně – a šíří se nenávist, mstivost,“ napsal …

16.07.2024

Heliodor Píka – celý život ve službě vlasti

V úterý 21. června 1949, právě v den výročí staroměstské popravy sedmadvaceti českých pánů, vyhasl na šibenici postavené v areálu věznice v Plzni na Borech život hrdiny a vlastence generála Heliodora Píky. Muže, jenž se tak stal jednou z prvních o…

15.07.2024

Psychologický syndróm obete

V psychológii existuje pojem syndrómu obete – je to stav, pri ktorom človek považuje seba za obeť negatívnych činov iných ľudí alebo okolností. To sa prejavuje nielen v vnímaní sveta, ale aj v správaní. "Obeť" obviňuje z príčin svojich problémov…

15.07.2024

Rozhovor. Na Spiši bola v uhorských časoch taká chudoba, že Slováci chceli po príchode do USA zabudnúť na domov

Michael Kopanic Jr. sa narodil v americkom Youngstowne v roku 1954. Babka mu však inak ako „malý Michal“ nepovedala. Rozprávala totiž len po slovensky.

Kopanic je americký Slovák, potomok tých, ktorým sa na Slovensku hovorievalo „amerikánci“.…

Naše obce

Zobraziť galérieUjko Vasyľ

Ujko Vasyľ - vyznaňa:

-Jem už senior. Mam všytko, što jem choťiv maty jak puberťak, lem z 50-ročnym oneskoriňom/spizňiňom. Ne mušu chodyty do školy, any do roboty. Dostavam hrošy/penzyju. Ne mam zakazano vychodyty z domu, idu de sja mi lem zachoče. Mam občanskyj preukaz, pusťať ňa do všytkych bariv i korčem. Jem majiteľom šoferskoho preukazu, mam motor i komputer mam, dokince vlastnyj... Moji kamaratky už sja ne bojať, že pryduť do druhoho stavu/ostanuť hrubyma... A ne mam vyražky/broky/akne... Žyvot je prosto prekrasnyj...!

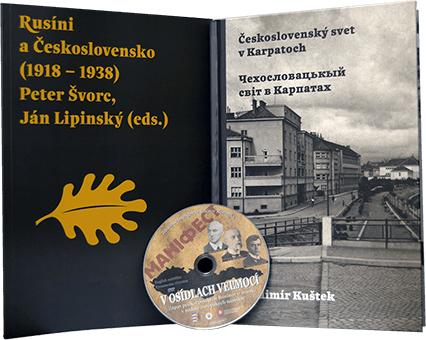

Československý svět v Karpatech

Československý svet v Karpatoch

Čechoslovackyj svit v Karpatach

Reprezentatívna fotopublikácia

Objednať