The incredible story of the mother of Andy Warhol, the King of Pop Art

How Ula went from a small village to America. Andy Warhol got his iconic typeface from her.

PETRA TOTH, a well-known jeweller and designer, followed in the footsteps of the mother of the King of Pop Art, Andy Warhol, from Mikova in the Stropkovsky district to Pittsburgh.

Andy's parents, Julie and Andrej, came from there and emigrated to the USA.

First Andrej in 1912, then Júlia Varcholová, née Zavacká, later Warhol, in 1921.

According to Petra Toth's notes, we have processed the most important moments in the life of the Warhol family.

Sweets

Andrij - Andrej Varchola was born in Mikova in 1886. Uľa was born in 1892 in Zavacká, Slovakia. She was one of fifteen children.

At that time Miková had less than 500 inhabitants, it was divided into Upper and Lower Miková. The people lived off the land, as was common not only among the Rusyns, and were engaged in agriculture.

The men earned their living by seasonal work on the dolniks and in other more fertile parts of the country. Over time, however, it became increasingly difficult to find work.

Both the Varchols and the Zavacks were among the wealthier families living in upper Mikova.

Julia admitted in one of her interviews that she only agreed to marry Andrej after he brought her a sweet during their courtship.

Andrej already had experience of working in America.

The wedding

The young couple were married in 1909.

"The wedding was wonderful, wonderful. I was dressed in white. I had a veil. I was beautiful. My husband had a white coat. Funny, funny. He had a cap with lots of ribbons. Three rows of ribbons. A day and a half with my mum and a day and a half with his mum. Big, beautiful party. Eating, drinking, barrels of whisky. Wonderful food, rice with butter and sugar, bread, good bread, home-made biscuits. Wonderful," 74-year-old Julia Warhol recalled in Esquire magazine in 1966.

Death, war

The Warhol family's first daughter was born three years after their marriage. But six weeks later the baby died of a cold. Andrei had already returned to America. Julia stayed with her in-laws and, like any bride, did the hardest work around the house.

The new times on the eve of war brought new and harsh punishments not only for desertion, but also for aiding and abetting desertion. Andrei and his brother managed to escape to Poland and then across the ocean.

Julia, who looked after her parents-in-law and younger siblings, felt the cruelty of the war at first hand. She had to hide in the woods, her house burned down and her mother died in the last year of the war. Andrei tried to send money to Julia in an envelope, but it always got lost on the way, he didn't trust the banks. As long as there was no war, money was sent by compatriots returning home.

"My husband is in America. I work like a horse. I live with his parents, the old people. I used to carry a sack of potatoes on my back. I just worked and worked. I was a very strong woman," Julie recalled in an interview.

For work

It is likely that Andrei visited America several times. The first time he travelled to America, he may have been about 17 years old and working as a miner in a coal mine in Pennsylvania.

Decades before the First World War, almost a third of the population of Mikhailovka had already emigrated to America. Emigration was the only way out of the impasse of their difficult lives. From every house in Mikova, at least one family member left to earn money in America.

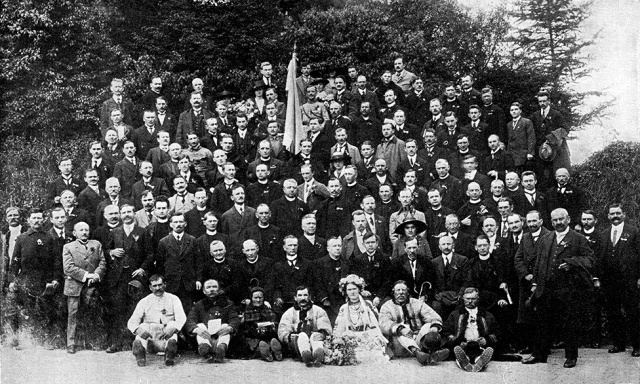

In three decades, Slovakia lost about half a million inhabitants to emigration. Between 1890 and 1914, some 225,000 Carpathian Rusyns crossed the sea and, like Andrei, settled mainly in the industrial areas of America.

Artistic skills

The Mikovtsy people were traditionally considered to be very skilled and resourceful. In addition to technical skills, the Varchol family were said to have immense intelligence, and the Zavatsky family were said to have artistic and musical talents.

Julia was a gifted singer in her youth, a "cantor" in the church. When the church in Mikova was being rebuilt at the beginning of the 20th century, Julia took a job as a helper, patiently mixing colours and assisting the master painters. Perhaps somewhere in Julie a love of art was born, which she later instilled with all her patience in all her three sons, especially the most gifted and youngest, Andy.

Gold on earth

In order to have enough money to travel to America, many Mikovians sold rolls to usurers and borrowed from relatives. At first, no one thought of staying in America permanently. America was as popular as seasonal work in the mines. They quickly learned the ropes, worked hard, and as soon as they had saved enough money, they returned to their families. With the money they earned, they bought a piece of land or built a new log cabin.

They also brought back new knowledge and innovations from America.

It is likely that the choice of which son would go to America was made by the parents themselves. The first emigrants from our area were mostly illiterate, which means that they could not read about America, the promised land, from pamphlets or newspapers. Letters from other emigrants played an important role, describing life beyond the Great Puddle in vivid detail. These letters would be read to the villagers by a teacher or vicar, and half the village would gather. It was almost a daily occurrence to meet agents in small villages, luring young men to America. They told stories of a rich continent where gold lay under the ground. All you had to do was bend down and pick it up.

In the late 19th century, men were paid one dollar for a shift in America, for example in a coal mine. A ticket in the cheapest class on a steamship to America cost $34.

Visas

Autumn had already begun to fall when, on 12 October 1920, the hard-working 28-year-old Julia Varcholova sat down at the American Consulate in Prague, wearing her business card, blouse, delicate cross-stitch embroidery, cap and a married woman's scarf. His office was in the capital of a new state called Czechoslovakia.

She hoped to meet her husband after many years. She obtained a passport with a photograph, or rather a visa to travel to America, valid for exactly one year. She had one year to buy a boat ticket and leave.

The journey

Time pressed on relentlessly. She was waiting for a letter from Andrew with instructions and money for the trip. He had tried to send her money several times, but it had always got lost along the way.

In the spring, Julia took action. Andrew sent her a letter with final instructions. It probably said in which Polish town, in which office selling ship tickets, a White Star Line boarding pass for the steamship Celtic to America was waiting for her. The city could have been Katowice or Auschwitz. Both were offices of shipping companies.

She borrowed the money for the trip from a mikveh priest and promised to name her first-born son after him - Constantine, a promise she did not keep. However, she sent the money to the priest as soon as she arrived in America.

In Poland

In early June 1921, Julia packed up her belongings and said goodbye to her home village for the last time. She took a carriage to Medzilaborce, a station 15 kilometres away.

From there she changed trains through the Lupkovsky Tunnel to Krakow and then on to Katowice or Auschwitz. There was an office where she was to pick up her boarding pass for the steamer to America. Julia was travelling with another Mikov woman, Mrs Prekst. The two brave Mikovtsy women arrived at the office in Poland full of enthusiasm, but a bitter disappointment awaited Mrs Prekstová. She had not bought a ticket.

Twenty-nine-year-old Julia made the arduous journey alone with her visa, boarding pass and some money.

The boat trip

Julia travelled by train to Gdansk. From there, the Belgian company Red Star Line ran a regular service taking passengers from our territory and Poland to Antwerp or Ostend. In one of these Belgian cities, Julie transferred to another shuttle, the Belgium Mail mail steamer, which took her to Dover, England.

There, thanks to digitalisation, we have proof of Julie's journey: she arrived by Belgian ship on 11 June 1921.

On board the Celtic, a large number of Czechoslovakians travelled to America for nine days. The Statue of Liberty was the first thing the new inhabitants of America saw. Julia set foot on the American continent on 20 June 1921 and never physically returned to her homeland, although she kept in touch with Mika throughout her life.

She died

Most emigrants travelled third class to America. It was below deck, often below sea level. It was overcrowded, dirty and cramped.

Between 1815 and 1930, 60 million people left Europe, 32 million of them for the USA.

More than 600,000 people emigrated from Slovakia in this wave.

The administrative procedures on Ellis Island, where immigrants were rounded up after disembarking, were often cruel and inhumane. The process was long and humiliating. At the slightest sign of illness or discomfort, the doors to America were closed and the tired, exhausted and emaciated immigrants were sent back to Europe at the shipping company's expense.

The fate of each man was decided by a single official, who allowed only the healthy and strong to enter.

One of them turned Ulya Varchol into Julius Warhol.

Together at last

Julia did not stay long in New York. She travelled eight hours to the industrial city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 600 miles away, where her husband worked. As she stepped off the train, a pall of acrid smog enveloped her.

Andy Warhol called his hometown 'the worst place in the world'. If you went out in a white T-shirt, it turned dark grey. In his 36 years as an artist in New York, he never once visited his hometown.

When Julie was 29 and Andrew 35, the couple were given a second chance at a life together.

A shared home

Andy's father, Andrew, became a proud official American a few months before Andy was born. Andrija Varchola became Andrew Warhola.

He worked in the ironworks of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. At first he was unable to find accommodation in a neighbourhood called "Rusyn Valley" (our way of saying "Rusyn Valley"). It was inhabited by Slavs who called themselves Ruthenians or Rusyns or Rusnaks.

The first dwelling of the Warhols was in Orr Street. It had two rooms and was on the second floor of a wooden terraced house. The water was cold and the toilet was outside. It was in this flat that Julie gave birth to Paul, John and Andy. The last Andy, who went on to become one of the world's most famous artists, was born when she was 36.

Now the house is unoccupied, neglected and derelict.

The theme of roots

Within two years of Andy's birth, the Warhols moved twice on the same street. The three boys slept in the same bed. As brother John said, they never felt poor; everyone around them lived exactly the same way.

They lived with another family in the house they moved into, paying $18 a month, which was about a quarter of the family's monthly income.

Andy Warhol studiously avoided the subject of his roots in interviews. When he applied for a job at a magazine in 1949, the editor asked for his CV.

"My life doesn't fill the size of a small postcard," he replied.

He also often lied about his date of birth. Once he said he was born in 1929, then in 1930 and sometimes in 1933. He also lied to his doctor about his date of birth.

She is interesting

Julie made soup from water, leftover ketchup and spices. When they could afford a house and garden, she grew tomatoes and root vegetables. They kept chickens in the garden and had home-laid eggs. The family also made their own 'kolbasi'.

A few days after Andy's sixth birthday, the family moved to Dawson Street.

The house was tiled on the outside, had a garden and a bathroom. In today's money, it was worth three years' work for a man. Andrew had a reputation for thrift. He repaired his three sons' shoes himself. Julia helped the family budget by cleaning houses for wealthier Jewish families and peddling various products.

She kept the boys busy with artistic activities. She rewarded good drawings with sweets and made sure there were always art supplies in the house. They looked for inspiration in magazines or football cards. Andy liked to draw flowers, butterflies and angels. These were the angels he recognised from his talented mother's drawings.

When critics wanted to write a book about Warhol, the artist resisted: "The book should be about my mother, she's so interesting.

Temple

The Warhol home was close to their family church, the Byzantine Catholic Church of St John Chrysostom. Located at the bottom of the hill in 'Russian Valley', the family visited it every Sunday. It was in this church that the future famous artist was baptised.

The historian Martin Javor, who not only founded the Kasigarda Emigration Museum (Kasigarda is the Slovak spelling of the English Castle Garden, the main gate of the New York Immigration Department through which every immigrant had to pass in the days before the construction of the reception buildings on Ellis Island), has mapped all the churches built by Slovaks in America.

There are 720 temples in North America.

Privileges

Andy was sickly from an early age. Perhaps when Julie saw that he was still ill, she was afraid that history would repeat itself and she would lose another longed-for child. As a result, Andy had special privileges in the family and spent much of his childhood in bed in his mother's care.

We now know that Andy suffered from a condition called PANDAS. It is an autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection. One of the symptoms is extreme attachment to a parent. Andy used to sleep in bed with his mum in the dining room, the other brothers upstairs with his dad.

"My mother read books to me in English with a thick Czechoslovakian accent as best she could, and when she finished I'd say 'Thank you, Mum' even though I didn't understand a word.

Andy spent most of his time in his room in bed with the radio on. "Andy always wanted pictures and drawings. I would buy him comic books," Julie recalled in an interview with Esquire magazine.

Without her husband's knowledge, she pawned her earrings and bought her youngest son a projector for nine dollars.

The death of her father

In a time of recession and economic crisis, Julie tried to make as much money as she could. As well as cleaning and door-to-door selling, she looked for other creative ways to make a living. She cut bright flowers out of peach cans and sold them for pennies to save money to buy her son new trainers.

Andy later admitted that these flowers were his main inspiration for one of his most famous pieces, Campbell's Soup.

When Andrew's father found a new job with a company that moved houses across America, tragedy struck. According to family legend, he drank from a poisoned river in Virginia in 1942 and died a long and painful death from poisoning.

The official autopsy report, however, disproved the family legend. The cause of death was tuberculosis.

Andy was 13 at the time.

The cancer

A few months after his father's death, the eldest son got married. The expectant couple moved to the top floor of the house, paying rent to Julie.

To make extra money, the family rented out one of the rooms to returning soldiers for five dollars a month.

When Julie was 51, doctors discovered she had colon cancer.

The sons visited their mother every day, and perhaps that's where Andy's almost panicky fear of hospitals comes from. Surgery saved Julie's life, but the older brothers had to take on the responsibility of running the household and caring for their younger sibling.

Songs

Perhaps influenced by her husband's death and serious health problems, Julia Warhol, who had been an official citizen of the United States for several years, decided to clean up the family estate in her home county.

Together with her sons, she renounced her inheritance of land and property in favour of her younger sister Eva. She was in constant correspondence with Eva. She sent her parcels, postcards, letters with drawings and photographs.

As a gift for Eva, Julia recorded Ruthenian folk songs in a recording studio and added a spoken commentary "our way" to each song. Decades later, thanks to a twist of fate, the record was digitised in Slovakia.

She cooked and cleaned

One winter in 1952, Julie went to visit her then famous and very busy youngest son at his home in New York.

She recalls finding 97 unwashed T-shirts in her wardrobe when she arrived. For almost two years, she became an integral part of her son's daily life.

"More amazing than possible, much smarter than Andy," is how Joseph Giordano, who used to visit Andy's house, described Julia. He was the only one who saw her as the source of the artist's problems, but also as the source of his inspiration.

All of Warhol's acquaintances were astonished by her presence in the house. She cleaned, cooked 'Czechoslovakian meals', even though Andy always presented himself in the media as a proud American who loved white bread and milkshakes. For dinner, Julia cooked cabbage dishes and the very popular "Czechoslovak stuffed pancakes" for guests.

Iconic calligraphy

Andy appreciated his mother for her artistic creations. "Very good and correct, not primitive".

Her absolutely iconic calligraphy, which she used to describe Andy's artwork, was not her own.

In fact, Warhol's father and other Rusyns had taught her to write with a steel pen dipped in ink.

Her handwriting, mistakes and all, was a perfect complement to Warhol's style.

Julie's handwriting played an important role.

In 1957, Julie wrote in cursive on all of Andy's important commissions.

She created her own alter ego, which she called Moondog.

Moondog's short story, written in Julie's signature calligraphy, is about a blind outsider and a homeless man.

Julie's unique handwriting in Moondog even won an art print award.

However, the winner was not Julie herself, but "Andy Warhol's mother".

In fact, many people thought it was Andy's alter ego who had entered the competition, rather than Andy's real mother.

In time, Andy and his assistant learnt Julie's calligraphy and continued without his mother's presence.

Proximity

Julie became increasingly withdrawn.

"Mrs Warhola was not charming, and I think Andy was somehow ashamed of her. But if you met Andy's mother, you'd know he liked her very much," said his friend.

"My son works a lot, is home a little and travels a lot by plane," Julie complained in a letter to her family.

Even the presence of many cats, most of them named Sam, couldn't fill the void in her home.

Perhaps it was during this period of complete solitude that Andy's most famous drawings, "Holy Cats by Andy Warhol's Mother", were created.

"I'm not that close to my mother, a lot of people like her better and get along with her better, they prefer to talk to her," Andy confessed to a friend.

On 3 June 1968, another tragedy struck Julie. Andy was shot by a crazed former actress from his films. Andy narrowly escaped death.

His death

In Andy's personal diaries, which he recorded over the phone to an assistant, he mentioned his mother only in passing. If at all.

Towards the end of her life, Julie was suffering from incipient dementia and her presence was a drain on her son's energy.

The brothers decided to move their mother into a nursing home. The bills for the new home were paid in full by Andy.

"I don't think your mother will be on this earth much longer. I look forward to hearing the news when you honour your mother's last wish in this world, to see her son one last time. Yours!" Andy's cousin wrote in a letter after visiting the nursing home.

Julie's final wish was never fulfilled.

On 28 November 1972, shortly after her 80th birthday, Julie Warhola died. Andy was too nervous to attend the funeral. He reminded his brothers to try as hard as they could to keep their mother's death a secret from the public.

Julia Warhola is buried with her beloved husband in the same grave in Pittsburgh Cemetery. A few dozen centimetres away, right in front of the caring mother, lies the grave of her famous son.

Jana Otriová

Editor

translation by deepl com

Aktuality

Zobraziť všetky30.05.2024

2% z Vašich daní

Uchádzame sa o Vašu priazeň...

Uveďte naše o.z. do svojho daňového priznania resp. vyhlásenia a my Vás potešíme knižným darom.

Notársky centrálny register určených právnických osôb

Informácie o určenej právnickej osobe

Evidenčné čí…

30.04.2024

Eugen Gindl: Československý svet v Karpatoch (recenzia)

Po každom veľkom dejinnom zlome sa učebnice dejepisu prepisujú. História etník, národov, štátov, ba i celých kontinentov sa rekonštruuje, dopĺňa, retušuje, ba v niektorých prípadoch (skoro vždy dočasne) sa niektoré kapitoly histórie aj gumujú. V…

30.04.2024

Stanislav Konečný: Začleňovanie územia Rusínov do rámca ČSR (1919 - 1920)

Od leta 1919 bolo evidentné, že vzhľadom na vývoj medzinárodnej situácie a stanoviská rusínskej reprezentácie doma i v Amerike stalo sa pripojenie územia juhokarpatských Rusínov k Československu jedinou alternatívou. Pravda, zostávalo ešte veľa …

27.04.2024

Politický monsterproces: Väzeň Husák svojich mučiteľov vytočil

Čo priznal, vzápätí odvolal

Všetci buržoázni nacionalisti sa dopustili najťažších trestných činov. To bola kľúčová veta obžaloby v kauze Gustáv Husák a spol. Čoskoro uplynie 70 rokov od konania tohto politického monsterprocesu. Súdne pojednávan…

25.04.2024

Čaputová počas návštevy Prešova: Kanceláriu prezidenta nezamknem, neberiem ani kľúče

Akúkoľvek diskrimináciu považuje za neprípustnú.

PREŠOV. Rozlúčkové turné prezidentky Zuzany Čaputovej po slovenských regiónoch pokračovalo vo štvrtok v Prešove. Navštívila radnicu, rusínske divadlo, evanjelické gymnázium, azylový dom i múzeu…

25.04.2024

Virológ Borecký – vedec, profesor, akademik s rusínskymi koreňmi

25. apríla uplynie sto rokov od narodenia významného virológa, imunológa a dlhoročného šéfa Virologického ústavu SAV Ladislava Boreckého, ktorý pochádzal z Uble, z rusínskej rodiny na Hornom Zemplíne.

V lete 1904 prišiel do Uble na Hornom Zempl…

Naše obce

Zobraziť galérieUjko Vasyľ

Vasyľ:

-Prychodžam domiv zo služobky, nožyky - poostreny, panty - nasmaruvany, kohutyky - opraveny, Paraska - hruba...

Československý svět v Karpatech

Československý svet v Karpatoch

Čechoslovackyj svit v Karpatach

Reprezentatívna fotopublikácia

Objednať